At Seedhouse, we’re endlessly curious about material innovation. Sometimes that means looking forward—and other times, looking back. The story of feed sacks is one of the most fascinating intersections of packaging, design, resourcefulness, and style in American history.

From Barrels to Bags: The Birth of the Feed Sack

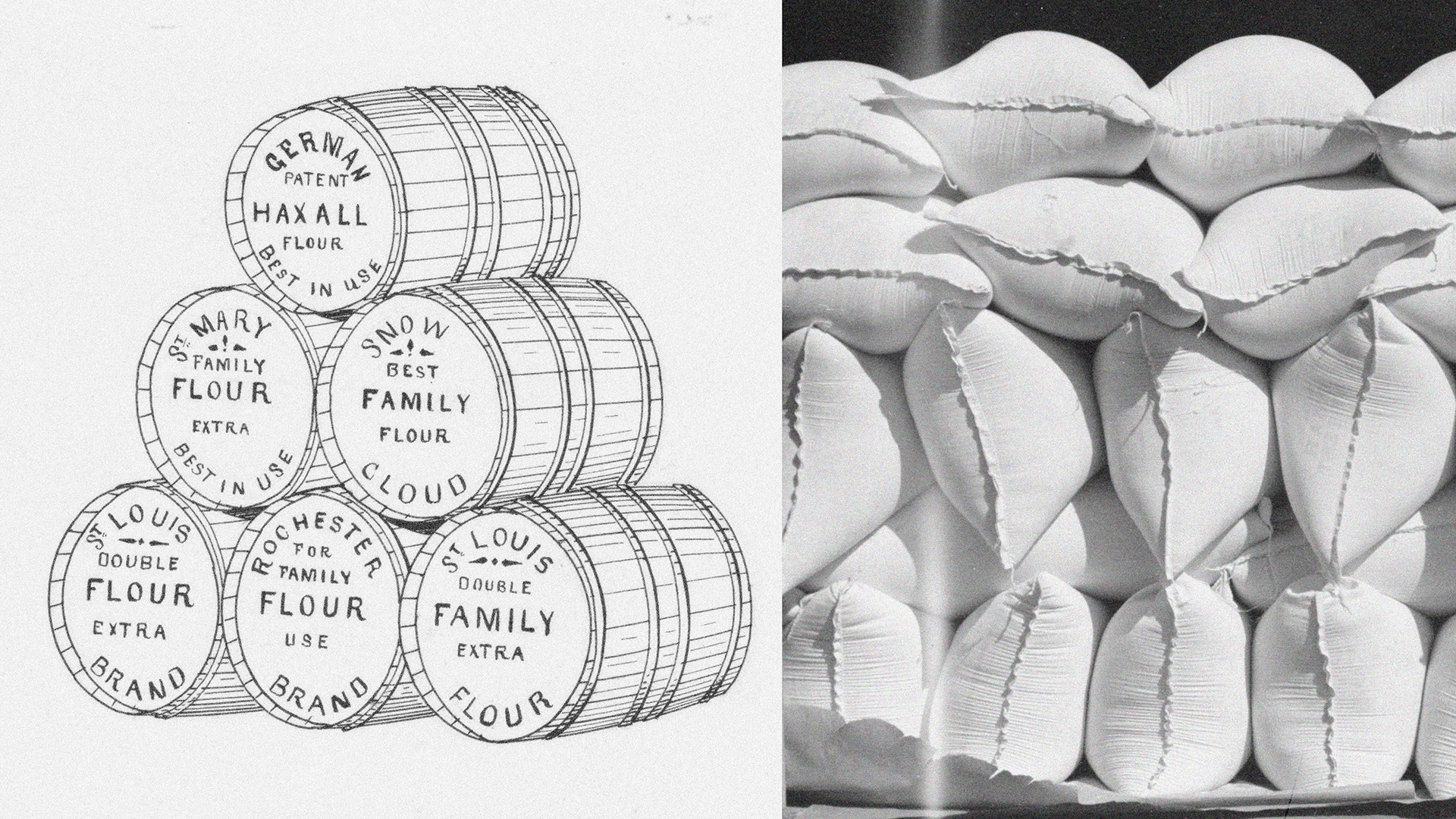

Before the mid-19th century, flour was sold almost exclusively in heavy wooden barrels. That began to change with the Industrial Revolution. As woven cloth became more affordable, manufacturers started experimenting with woven sacks.

Two advancements accelerated the shift:

- 1849: Henry Chase, founder of the Chase Bag Company, and inventor John Batchelder developed a chainstitch machine-sewn flour bag.

- 1864: J.M. Kurd patented a machine that could mass-produce sacks, meeting wartime demand during the Civil War.

By the 1880s, flour mills were printing their names on the bags—an early form of branded packaging. One bag in the Smithsonian bears an 1890 copyright date. And the earliest logoed bags? They featured a mule, created for Ralston Purina.

The Accidental Birth of a Fashion Trend

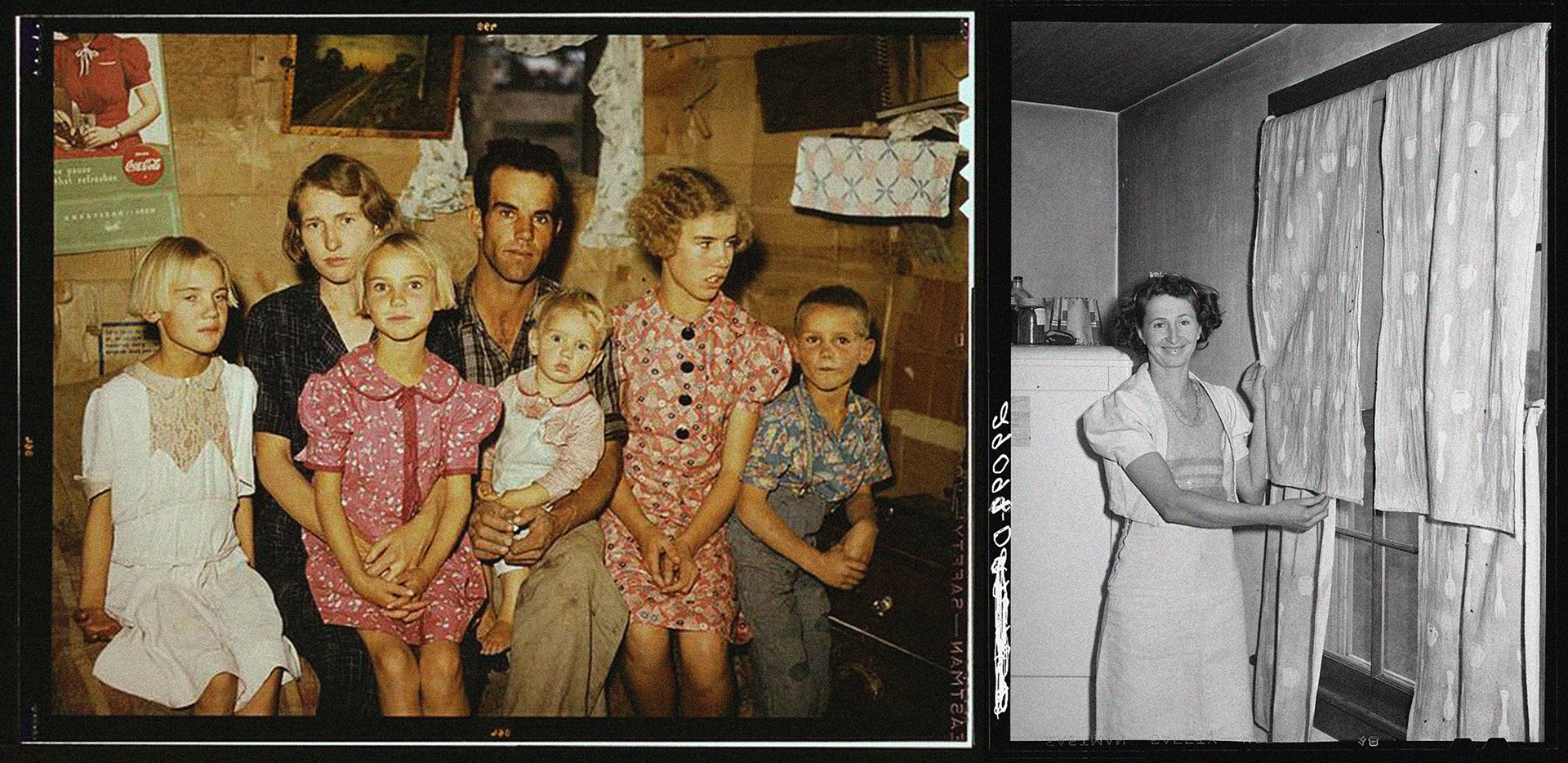

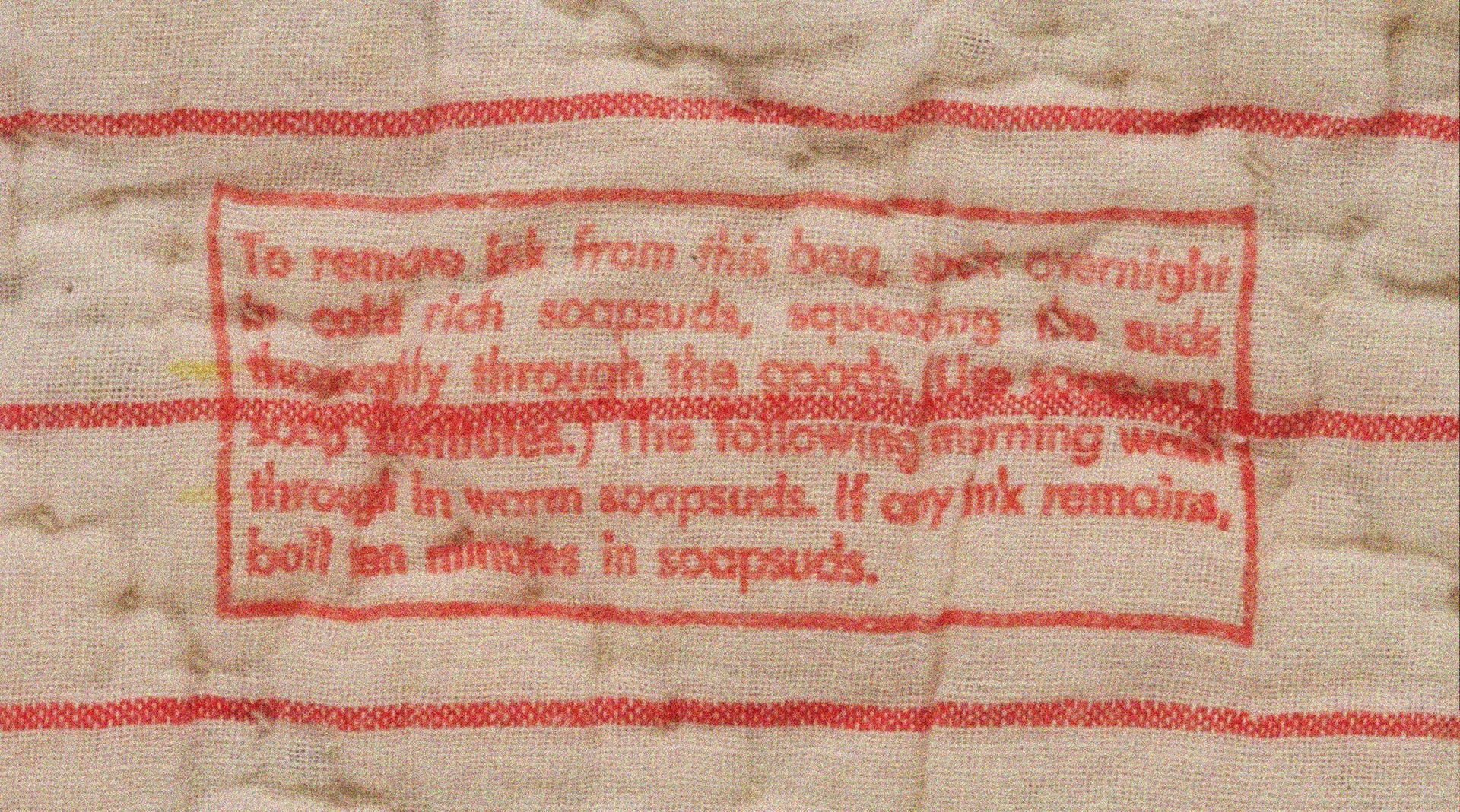

Cotton feed sacks weren’t meant to be beautiful; they were meant to be functional. But rural families quickly realized that the sturdy cloth could be sewn into clothing, quilts, dishtowels, and more. In the early 1900s, women washed the ink out and used the plain fabric however they needed.

Dress Print Bags: When Packaging Companies Became Pattern Designers

Realizing their bags were being repurposed into clothing, companies made a bold innovation: print the sacks with patterns women would actually want to wear.

In 1937, the Percy Kent Bag Company pioneered the “dress print bag”, offering florals, stripes, plaids, and novelty prints designed specifically for fashion. These became especially popular during and after World War II, when fabric was rationed.

Choosing the prettiest feed sack became a small but meaningful act of personal style.

Chicken Linen: A Rural Economy of Its Own

Feed sacks weren’t just practical. They became currency. In rural areas, especially in the South where poultry farming boomed after WWII, “chicken linen” created its own micro-economy. Women who bought more feed (and therefore had more sacks) often sold extras to neighbors for 20–25 cents apiece.

As one Georgia poultry grower recalled, neighbors would come over to choose patterns, just like selecting bolts of fabric. For a brief moment in time, women—who had little financial autonomy—controlled part of this changing economy. The feed sack had gone from packaging to product.

From Necessity to Nostalgia

By the late 1950s, cotton sacks gave way to cheaper paper and plastic packaging. But the legacy of feed sack fashion lives on. Collectors, quilters, designers, and museums (like the International Quilt Museum’s exhibition “Feed Sacks: An American Fairy Tale”) continue to celebrate the material’s beauty and cultural significance.

What started as a simple improvement in packaging technology became a symbol of resilience, creativity, and American ingenuity.

Material Innovation

Designers know: materials matter. And sometimes the most forward-looking innovations come from understanding how people adapted, reused, and reimagined what they had.

Feed sacks remind us that:

- Good packaging can have a second life

- Design responds to culture (and vice versa)

- A humble material can spark joy, creativity, and economic opportunity

At Seedhouse, we’re always searching for new—and sometimes old—materials that can serve our clients in unexpected ways. The story of ‘chicken linen’ and ‘glad sacks’ is a reminder that great packaging doesn’t end when the product does. Sometimes, that’s where the magic begins.